Mutations in the gene PTPN11, which encodes a common enzyme called SHP2, can result in developmental disorders, such as Noonan Syndrome, and act as oncogenic drivers in patients with certain blood cancers. Due to the well understood role of the enzyme SHP2 in Noonan Syndrome and in tumorigenesis, many companies are currently trying to develop drugs that inhibit the enzyme. However, it is unclear what impact mutations to SHP2 may have on the potential efficacy of drugs targeting this enzyme. Using the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS), researchers investigated the effect that the most frequently observed mutation of PTPN11, E76K, has on the structure of SHP2 and its allosteric inhibition by SHP099. They found that SHP2E76K adopts an open conformation, resulting in the elimination of the binding pocket for SHP099. Because the E76K mutation reduces the inhibitory potency of SHP099 for SHP2 by more than 100-fold, the researchers conclude that an effective allosteric inhibitor of SHP2E76K would need to exhibit at least two additional orders of magnitude greater potency than SHP099.

SHP2 has a relatively conserved structure and function. Structurally, SHP2 contains a protein tyrosine phosphatase catalytic domain (PTP domain), two SH2 domains (N-SH2 and C-SH2) and a C-terminal tail with two tyrosine phosphorylation sites. SHP2 activity is auto-inhibited by intramolecular contacts between its N-SH2 and PTP domains. Upon stimulation of receptor tyrosine kinases or cytokine receptors by their ligands, the SH2 domains bind to induced phosphotyrosine sites to induce a conformational change that unmasks the PTP domain to permit full catalytic activity of the phosphatase. Depending on the cellular context, the result is either physiologic activation of SHP2, or oncogenic signaling in tumors. As an oncogene, SHP2 regulates cancer cell survival and proliferation primarily by activating the RAS-ERK signaling pathway. Due to its role in tumor growth, as well as in T-cell inactivation, SHP2 has become one of the most important anti-cancer targets for the pharmaceutical industry. An allosteric inhibitor called SHP099 stabilizes SHP2 and is known to inhibit cancer cell growth both in vitro and in vivo.

Encoded by the gene PTPN11, SHP2 is ubiquitously expressed in the cytoplasm of many cell types and plays a regulatory role in various cell signaling events that are important for a diversity of cell functions, such as mitogenic activation, metabolic control, transcription regulation, and cell migration.

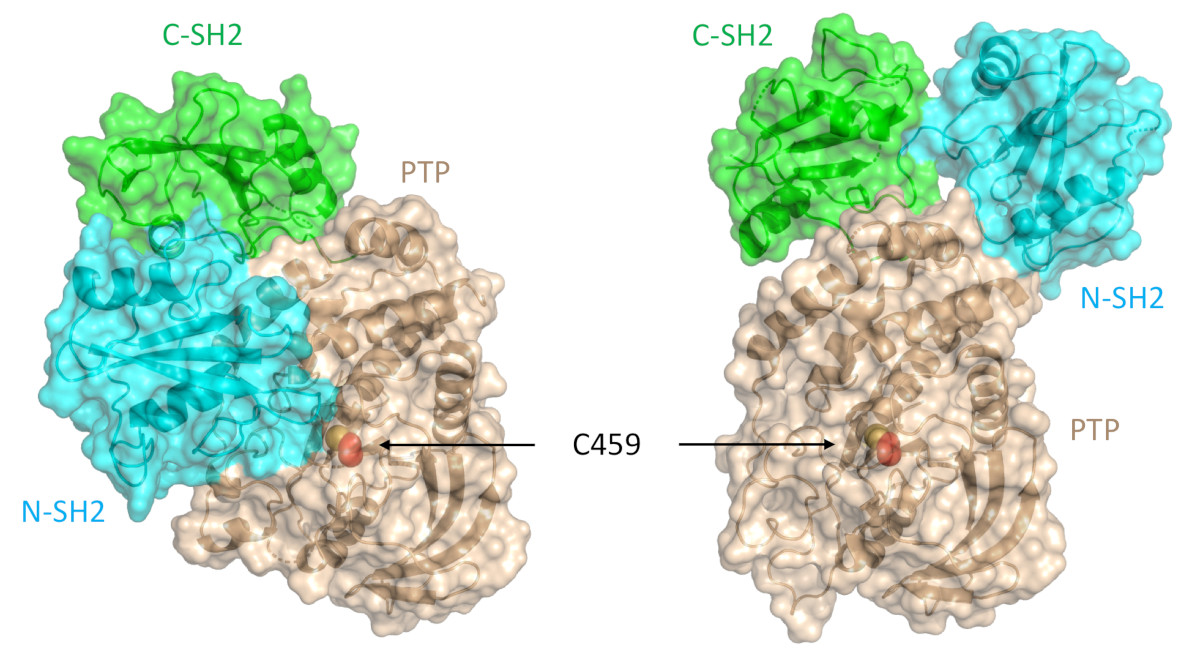

SHP2 contains two tandem SH2 domains (N-SH2 and C-SH2), a catalytic protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) domain, and a C-terminal tail that has at least two phosphorylation sites. This protein adopts a closed, autoinhibited conformation in which the N-SH2 domain engages the catalytic pocket of the PTP domain and physically occludes the active site. Normally, the binding of tyrosine-phosphorylated ligands to the SH2 domains is required to overcome autoinhibition, but oncogenic mutations of SHP2 destabilize the autoinhibited conformation and lead to enhanced activity.

Scientists have recently discovered allosteric modulators that stabilize the closed form of SHP2. One such compound, SHP099, acts as a molecular glue between the N-SH2 domain and the catalytic domain. SHP099 has been reported to exhibit antiproliferative activity in cancer cell lines that are dependent on SHP2. It remains an open question, however, whether common mutant forms of SHP2 can be allosterically inhibited by SHP099.

Researchers from the Harvard Medical School, the Dana Farber Cancer Institute, and the Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research investigated the impact of PTPN11 mutations on the structure of SHP2 and on allosteric inhibition by SHP099. Using data obtained via x-ray small-angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) macromolecular x-ray crystallography experiments performed at the Industrial Macromolecular Crystallography Association Collaborative Access Team (IMCA-CAT) beamline 17-ID-B at the APS, they found that the most frequently occurring SHP2 cancer mutation, a potent E76K substitution, results in a 120-degree pivot of the C-SH2 domain and relocalization of the N-SH2 domain to an alternative PTP domain interaction surface. This more open conformation of SHP2, confirmed using size-exclusion chromatography-SAXS experiments performed at the Bio-CAT beamline 18-ID-D at the APS, results in the elimination of the binding pocket for SHP099 and, ultimately, a 100-fold decrease in the allosteric inhibitor’s potency toward the E76K mutated enzyme (Fig. 1). (The APS is an Office of Science user facility at Argonne National Laboratory.)

One conclusion to draw from these results is that because a significant number of patients with PTPN11-mutated cancers bear the E76 mutation, any potential allosteric inhibitor for these patients would need to exhibit at least two additional orders of magnitude greater potency than SHP099. An effective allosteric inhibitor would also require a longer target residence time to achieve successful suppression of SHP2’s tumorigenesis activity. Alternatively, effective therapies employing multiple allosteric inhibitors to target more than one distinct pocket on SHP2 could halt or slow tumor growth associated with this protein.

Adapted from an APS article by Chris Palmer

See: Jonathan R. LaRochelle, Michelle Fodor, Vidyasiri Vemulapalli, Morvarid Mohseni, Ping Wang, Travis Stams, Matthew J. LaMarche, Rajiv Chopra, Michael G. Acker, and Stephen C. Blacklow, “Structural reorganization of SHP2 by oncogenic mutations and implications for oncoprotein resistance to allosteric inhibition,” Nat. Commun. 9, 4508 (2018). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-06823-9