Storing the Power to Fly

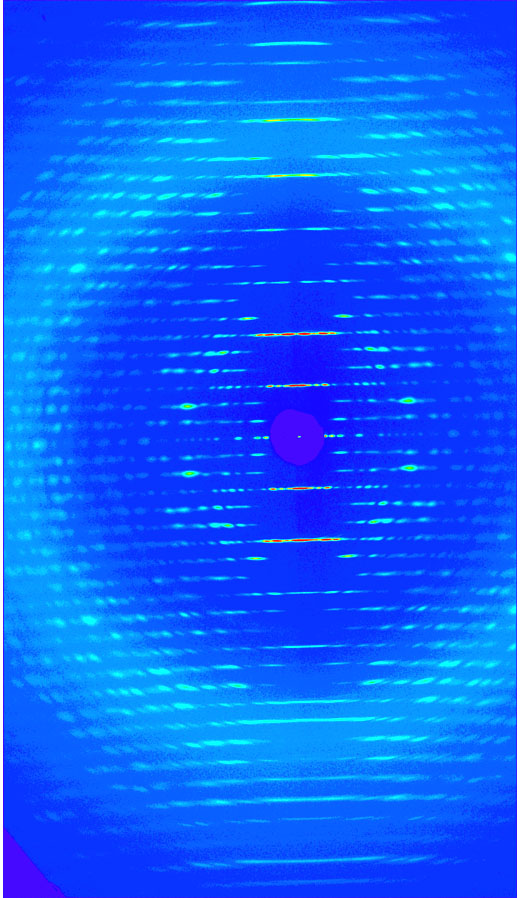

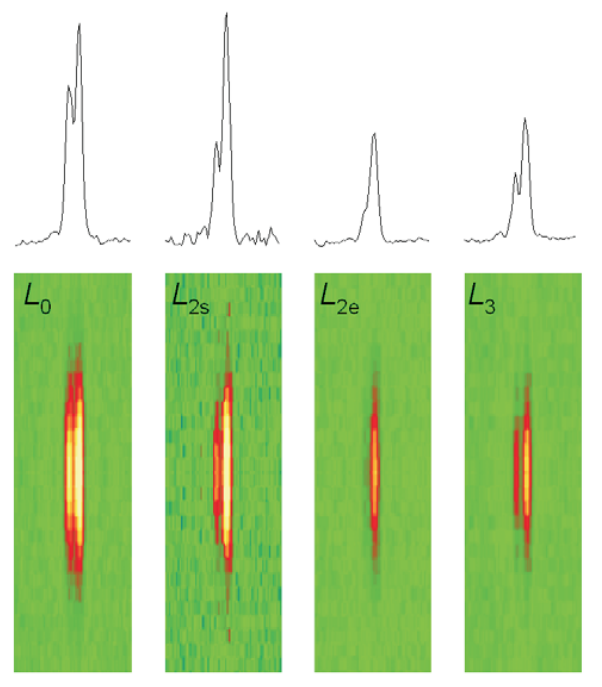

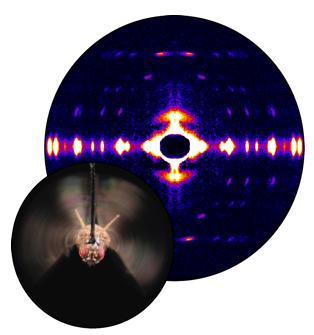

Fruit flies beat their wings faster than their cellular powerplants can generate the energy needed for flapping. To resolve this energetic discrepancy, researchers from the California Institute of Technology, the Illinois Institute of Technology, and the University of Vermont used the BioCAT beamline 18-ID at the APS to obtain a series of x-ray photographs that revealed the flies’ secret: A muscle protein used to power wings acts like a spring, storing energy while stretched before snapping back. Not only did this finding surprise researchers who study muscle, but the results might also help scientists better understand the human heart.

Drosophila, the fruit fly, beats its wings up and down once every 5 milliseconds. Two layers of muscle control this action: when one layer contracts, it stretches the other. The stretched muscle is then primed to contract; when it does, it stretches the first layer and completes the cycle. These cycles occur faster than nerve impulses can stimulate them; hence, the muscles themselves must keep the beat going.

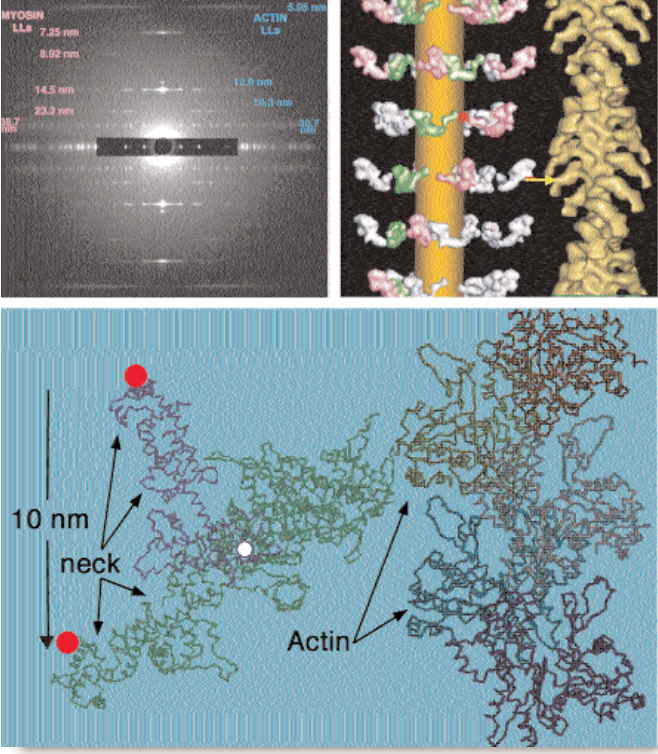

To find out how muscles do this, the research team needed to visualize the proteins that make muscle contract. Within the flight muscle cells, two proteins cooperate to do this. Myosin proteins …